“Are you hungry?”

“Are you hungry?”

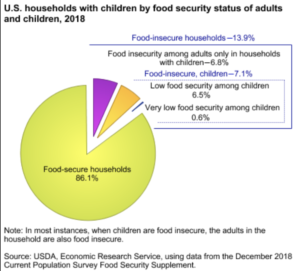

In 2015, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended, for the first time, that pediatricians should screen all children for food insecurity. Back then, an estimated 7.9 million kids in our country lived in “food insecure” households. Unfortunately, we haven’t moved the needle much on the number of kids and families sometimes going hungry. In 2018, the USDA reports that 13.9% of American households were food insecure.

According to Feeding America, the food insecurity rate in West Virginia is 14.8% in 2017. And the percentage of West Virginia’s kids? 20.6%

So what exactly does the term “food-insecurity” mean and what are the consequences of living with it? The USDA defines the phrase as “a lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life,” and “the disruption of food intake or eating patterns because of lack of money and other resources.” It adversely affects our health from cradle to grave.

For kids, food insecurity can be stigmatizing and a major factor in a student’s inability to thrive academically.

When we initiated plans to launch Think Kids, we talked with UniCare about the social determinants of health, prevailing challenges here in West Virginia to improving kids’ health, and what issues they’d like to tackle moving forward. They identified food insecurity, and so we took a dive into research evidence published over the last 10 years– specifically, if providers are screening their patients for food insecurity, and if so, how?

The results were a mixed bag.

In fact, just this month, a research article was published in Health Affairs that shared collected qualitative data from twenty-two accountable care organizations (ACOs). Researchers came to this conclusion: “The ACOs with an emphasis on social services in our sample were struggling to address social determinants of health, despite serving populations with significant social needs and having leaders who recognize the importance of social determinants and facilitate the integration of social services and medical care.”

It’s here where we find ourselves at the launch of The Health and Hunger Project– initiating and facilitating a dialogue to better integrate health care and social services on the community level. Our first step begins with assessing if primary care providers in West Virginia ask their patients if they are food insecure, if they don’t, why not, and if they do, what they do about it. If you know a primary care provider, or someone who works in the primary care setting, please encourage them to take the survey. It only takes about 3 minutes to complete.

Next step, we’re going to survey community resource providers who address food insecurity, like food banks, pantries, backpack programs, etc. We’re going to ask: Do you know and work with your local doctors, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and nurses? Do they know about your services? Refer patients to you? And so on.

We’ll use this information to inform our panel discussions at the upcoming Health and Hunger Summit, scheduled for May 5. If you’re a stakeholder in this effort, we encourage you to attend. It’s free, and we hope to have a really robust, honest dialogue about how we can better connect health care to community resources that address hunger. Knowing the challenges we face in our state, it’s a large undertaking– to be sure– but an important one. We hope you’ll join us along the way. If you’re interested, share your name and email in the newsletter signup form on the right.

0 Comments