by Sarah Davis

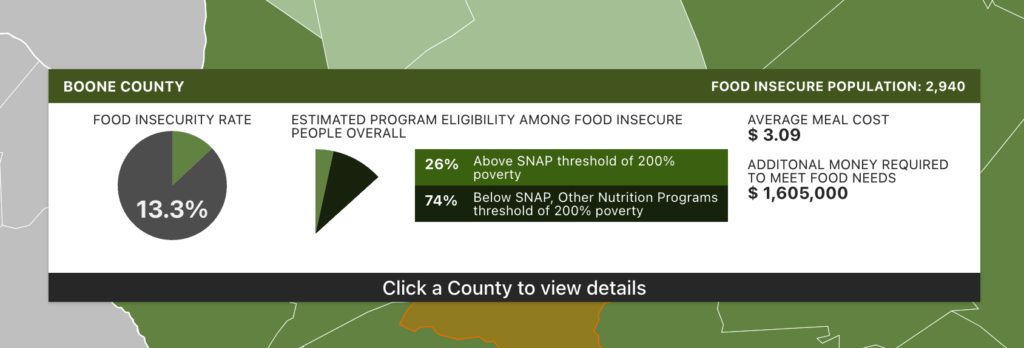

Where the average meal costs $3.09, Boone County is no stranger to food insecurity. According to Feeding America, 74% of the county’s population qualifies for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

Many of the communities in Boone County are considered food deserts, which means that large areas of residents have very limited accessibility to nutritious, affordable foods.

According to the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources, Boone County only has five grocery stores that participate in the WIC program: a Kroger in Danville, Little General Store in Comfort, Par Mar in Jeffery, Save-A-Lot in Danville, and The Country Store in Seth.

These five stores serve the 22,059 people who reside in the county. Among them, 17.8% of the population lives in impoverished conditions.

Many of Boone County’s residents rely on government programs and community resources to keep them afloat, both in health and in navigating the food deserts they call home.

One asset that Boone County has is West Virginia University Extension Services. In the Boone County office, a variety of services are offered to those in the community, including the Family Nutrition Program.

Heather Cook

Heather Cook, who serves as a virtual educator for the program, says that the primary focus is teaching adults and children the importance of nutrition.

“We talk a lot about physical activity and why it is important to move our bodies,” Cook said. “We talk about healthy choices; why it’s important to make them.”

In order to receive programming from WVU Extension, at least 50% of school students must be eligible for free or reduced-price meals. In October 2020, all eleven schools in the county were above 50%, the lowest being 78% at Scott High School.

Six of those schools were 100% in need with all children in those schools qualifying for free and reduced meal benefits.

In the county’s low-income elementary schools, children have the opportunity to experience a farmer’s market. The children typically receive anywhere from five to 15 pounds of fresh produce at these markets.

With the market, Cook teaches a companion curriculum that educates kids on where their fruits and vegetables come from. It’s called the International Junior Master Gardener® Program.

“It also gives them an opportunity to grow their own food as well,” she said. “If we’re talking about sweet potatoes, we look at the origin of where they come from, the different nutrients and vitamins that come in them and why they are so important to our bodies.”

When it comes to accessing these nutritional meals, Cook says that the communities of Boone County struggle to find them. In our conversation, Cook described her previous work in Whitesville.

“When I first started going to Whitesville, there was one grocery store; it was a Save-a-Lot, and it soon shut down after I started working,” she explained. “That little community either had to travel to Raleigh County– 25 minutes- to go to a Walmart, they had to travel into Madison, which was over 25 minutes, or they had to go out through Marmet and go to Charleston, which would have been over 25 minutes.”

She described Whitesville’s situation as a food desert with a lack of public transportation.

However, in recent years, a few dollar stores have populated the area. Cook says that the new food sources are improving their nutritional values.

“Thankfully, we’re seeing a lot of changes within dollar stores where they’re having refrigerated and frozen sections,” she said. “Some are starting to provide produce that’s fresh.”

During the coronavirus pandemic, Cook and the WVU Extension Services collaborated with food pantries to combat food insecurity in the county.

“I think the pandemic was a huge hit and huge loss to everybody,” Cook said.

In addition to WVU Extension and the family nutrition program, Boone County residents can utilize Cornerstone Family Interventions, a resource center made up of two outreaches: the Cornerstone Child Advocacy Center and the Parents as Teachers program.

Monica Ballard-Booth

Monica Ballard-Booth, the center’s executive director, says that they see hungry children and families in both programs.

“That’s something that we do track,” she said. “We do see neglect as well, including kids who talk about being hungry.”

When it comes to combating hunger, Cornerstone collaborates with other organizations to provide sufficient assets to the people of Boone County. During the initial wave of the coronavirus pandemic, Cornerstone remained open. Meetings with children and their families were held virtually and food insecurity became more evident.

With the pandemic officially ending in May 2023, the federal government started cut back on their food assistance programs, meaning those who received extra food stamps and other resources now have to adjust back to pre-pandemic funds.

“We did see a lot of people during the pandemic who had access to more food stamps,” she went on to say. “Those were increased for a lot of people. I think some people became reliant on it and now that they’re getting cut, they’re used to spending more.”

Some of the families receiving additional SNAP funding, according to Ballard-Booth, did not use them towards nutritional food for their children.

“Even though they were getting food stamps, we still had children telling us that they weren’t being fed,” she said. “So, we knew that there were resources coming in for those families, but they didn’t always spend those on the children.”

They also saw a lot of working families struggle with the rapid increase of food prices.

“I think more of the people who faced hardship with that were those people who were working more and then they saw all those prices go higher and higher,” she said. “Those people struggled more than the ones who maybe needed the food stamps.”

Cornerstone has a diaper pantry, a place where those in need can get diapers and formula.

The center would like to have an on-site food pantry, but the refusal of funds has made that difficult.

“We don’t have funding. Actually, we had requested funding a couple of months ago,” Ballard-Booth said.

They did not receive funding for a prospective food pantry.

Despite that, the Greater Kanawha Valley Foundation provided emergency grants to the center during lockdown. The center also facilitated support groups, a service that they still offer.

Ballard-Booth pointed out the lack of homeless and domestic violence shelters in the county.

“That was also a problem during the pandemic; when a lot of people, you know, needed some help and they couldn’t always get that in the county that they lived in,” she explained.

She also noted that many Boone County residents do not have access to public transportation, making it increasingly difficult to get the healthy resources residents need for themselves and for their families.

According to Ballard-Booth, the State of West Virginia has launched a new database system called ‘Find Help’ that the center can utilize to track their client’s referrals.

“We make every effort to make sure that they all get referrals,” she said. “That’s really important that they get that.”

In Boone County, 2,940 residents (13.3%) are considered to be a part of the food insecurity population.

Many of the people in Boone County rely on government programs and community resources to keep them afloat, both in health and in navigating the food deserts they call home. Community resources are available to help—resources that were available pre-COVID— but the same historic challenges still exist, like poverty and food deserts. In the end, COVID relief funding was a temporary boost but was never enough to meaningfully address the persistent obstacles in addressing food insecurity in Boone County.

Sarah Davis is a sophomore journalism student at Marshall University. She is the news editor with The Parthenon, Marshall’s student newspaper. She also has experience with the Charleston Gazette’s Flipside. Sarah enjoys reading, traveling, shopping and playing tennis in her free time. She is also an active member of her local church. Sarah aspires to work as a multimedia journalist and dreams of making it big someday.

1 Comment

Destiny · October 10, 2023 at 2:35 am

As a stay at home mom who’s husband just got a new job, he is now just barely making over the wage that considers us unable to qualify for snap. He makes $200 more a year than the yearly allowance. Snap is not adjusting to inflation of grocery prices or the “new” minimum wage of $15 an hour. This needs looked into.