Linda Higgs

Kelli Caseman

How do we address the inequity in West Virginia’s health care system experienced by kids with developmental disabilities?

That’s a really big question.

To begin the process of answering it, we first have to ask a series of smaller questions. Who are kids with developmental disabilities? What kind of health care do they need?

Even these questions can be hard to answer.

Developmental disability is a functional definition for a severe, chronic disability that is often present at birth but can manifest anytime prior to an individual’s twenty-second birthday. It is a mental or physical condition, or a combination of both, that causes lifelong substantial limitations in major life activities such as self-care, language, learning, and mobility. Some of the more commonly recognized developmental disabilities include autism, Down syndrome, spina bifida, and cerebral palsy. These children and teens often have complex, challenging health care needs, and these challenges can be incredibly complicated. Sometimes they can seem basic but persistent. For example, a child may need to see an out-of-state specialist for specialty care. Or, a family may have difficulty finding a local dentist with an accessible facility that has the training and ability to care for a child with an intellectually disability, or one with significant physical disabilities.

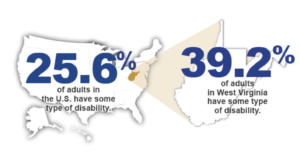

With so many conditions under the umbrella term of developmental disabilities, it’s hard to quantify how many children in our state have a developmental disability. Here is what we do know. According to the CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities, West Virginia has one of the highest rates of adults with disabilities in the country. A current estimate of the number of children and adults in West Virginia with developmental disabilities is 1.8%, or 33,000 individuals.

And according to the West Virginia Department of Education, there are 44,671 students with an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) about 17.7% of all West Virginia public school students in school year 2020-2021. In 2018-2019, the national average was 14% of schoolchildren had an IEP. While not all children with IEPs have been diagnosed with a developmental disability, collectively they comprise a substantial number of children with IEPs. Also, it is important to note that some children have 504 plans, and some have no education plan at all. Using aggregated public education data to count the number of school children with developmental disabilities remains problematic.

And so, without specific figures for how many children ages 0-18 have been diagnosed with a developmental disability, we know that West Virginia has a significantly higher number of school-aged children and adults who are identified under this larger term of developmental disabilities than the national average. It’s a large part of our state’s population– our counties and communities. For many of us, they are our own children, our cousins, our friend’s children, our neighbors, members of our church, and so on. We strive to create inclusive communities and schools for children and teens, but how inclusive is our health care system?

Both of us have worked for many years with families and the health care system in our state, and when it comes to addressing the specific challenges children with developmental disabilities have when accessing health care, we know that there are overwhelming, unmet needs that parents and caregivers face. We hear it often. The health care system isn’t structured to meet the specialized needs of this population of children. Assessing and articulating these challenges are important first steps to addressing systemic inequities and building a more responsive delivery model for West Virginia’s kids.

Think Kids, with support from the West Virginia Developmental Disabilities Council, launched a project this year to undertake this important work. You can learn more about it here. Our first step is to survey parents and caregivers about their experiences in accessing health services. Here are some of the things we’re hoping to learn:

- Do parents/caregivers/families believe that the health care system is responsive and supportive to the health care needs of their children?

- How far do families travel to access health care– from preventive care like well-child exams and dental cleanings to specialty care, such as pediatric endocrinology, cardiology, or applied behavior analysis? Is transportation a challenge?

- Does their health insurance cover most of their health care services? If not, what doesn’t it cover?

- Do local primary care providers have the proper training and medical knowledge to care for their children? Have they ever had doctors or practices turn their children away for care?

- Do families believe that a consequence of fewer local services results in an over-utilization of the ER?

- Is keeping medical records intact possible? Does information easily flow between multiple doctors’ offices?

- Do insurance providers, doctors’ offices, or social support programs help provide care coordination? Once your child was diagnosed, did you receive help taking next steps to finding support?

- Importantly, do you feel valued and supported by the health care system?

Kids with developmental disabilities need health care for the same reasons anyone else does—to stay healthy, active, and a part of their communities. If you’re a parent or caregiver with a child or teen who has been diagnosed with a developmental disability, we’re sure you agree.

All children deserve high-quality, family-centered, integrated health services. We know that our state’s health care system is comprised of many quality professionals, struggling with limited resources in medically underserved communities. We know that even if we’re successful in garnering a robust response from families around the state, we are still facing the challenge of reforming the system. It will take a lot of work to build an equitable health care system for kids with developmental disabilities. If this work is meaningful to you, sign on to the project email list and get involved. Join Think Kids in taking the first step in a long, important journey.

Linda Higgs is a program specialist with the West Virginia Developmental Disabilities Council.

Kelli Caseman is the executive director of Think Kids.

2 Comments

Cindy · February 23, 2021 at 4:29 am

Thanks so much Linda and Kelli for speaking about this import issue. It is one of the most challenging barriers for parents. The other issue with finding specialized or just routine medical care for you child is the wait time to get in to see a specialist or physician that will see you is anywhere from 6 months to a year both in and out of state. Many group practices will not support their physicians in specializing in this serving this population because it often requires extended visits and that does not allow that physician to meet their billing quota. ?

ABA therapy Greater Toronto Area · August 3, 2021 at 7:05 pm

Together For Better Therapy offers Applied Behaviour Analysis (ABA) interventions and Speech Therapy to children in the Durham Region and the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) who have Autism, social communication disorder etc.