by Erin Beck, Kids’ Health Correspondent

National health groups have declared a mental health crisis among the nation’s children. What does that look like in West Virginia?

According to mental health professionals, adults aren’t detecting problems in kids soon enough, and there aren’t enough community-based options, such as local providers who can see kids on an outpatient basis and make in-home visits. The state lacks inpatient options, too, when symptoms get worse. So children are ending up in emergency rooms when early intervention is too late, and with nowhere to send them.

In 2019, I wrote for The Register-Herald that West Virginia planned to expand mental healthcare services for children and their families, following a U.S. Department of Justice investigation. The DOJ said West Virginia was keeping far too many kids with mental health problems far from their homes, in residential facilities and psychiatric hospitals, often out of state.

State officials announced they’d reached a memorandum of understanding with the federal government. They planned in-home visits, mobile crisis response teams, and wrap-around services, meaning caseworkers would not only evaluate children’s health, but also help with family problems like housing and financial instability. The goal was to prevent more severe mental health crises from occurring in the first place.

How kids are ending up in crisis

Healthcare providers made headway, according to interviews with several of them. But then COVID-19 happened.

Earlier this week, I described how disruptions to routine and instability resulting from the pandemic are contributing to more anxiety and insecurity among children.

Dr. Eric Limegrover, chief clinical officer for Westbrook Health Services, said structure and routine provide a sense of safety and security for kids.

“The absence of routine throws things into a state of chaos,” he said.

Kids feel a loss of control, because there’s no set end date. That sense “wreaks a lot more havoc for children than it does for adults,” he said.

It’s harder for them to focus on school as a result, according to Limegrover, so they become less engaged. And as kids have been isolated, they’ve also had to withdraw from extracurricular activities.

“And so with that, they start to mail it in,” he said.

When school is in session, kids come in contact with multiple teachers and other staff members during the day, so there’s a greater chance someone will notice warning signs. They also have more opportunity to build social connections.

Parents may not be prepared, or willing, to acknowledge signs of deteriorating mental health in their kids. And as kids spent more time at home, they built more negative coping skills, like spending too much time online.

I also wrote earlier this week about how political disagreements with parents and social problems, which kids often read about online, are affecting child mental health.

Limegrover noted that kids figure out futures and goals for themselves through their interactions with other people. And in greater numbers, kids don’t want to have those interactions with their family members. They’re frustrated with them.

He did see a sign of hope – a desire for connection.

“If anything, I think parents and children have become more appreciative of the school environment,” he said. “Absence makes the heart grow fonder.”

I reached out to DHHR earlier this week to check on the status of implementation of the 2019 memorandum of understanding, but haven’t heard back. I’ll update you if I do.

Morgan Blatt, of Prestera, told me about a substance use disorder grant that allows her to work with the whole family. And leaders at Prestera and Westbrook both mentioned mobile crisis response. So some of the promises seem to be taking place.

But Limegrover said across the state, hospitals are seeing kids come in with much more severe problems, including those with suicidal thoughts, and too late for early intervention.

“There are absolutely no kid residential placements right now,” he said. “And that is a very big issue that I know multiple different state departments are taking a look at because unfortunately, they’re having difficulty managing these kids safely in the community, especially with the limited provider network that we have, and also the need that they have now – more than just outpatient counseling can handle.”

Emergency room visits for kids in crisis are increasing across the country, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics declaration of a child mental health emergency.

A lack of treatment options

Dr. Lauren Swager, division chief for child and adolescent psychiatry at WVU Medicine, said she agreed with the DOJ’s assessment that too many kids were being sent to residential care instead of being cared for in their own communities, close to social connections.

“But when the culture of sending kids to residential has been present for years it is hard to change behaviors, and the system also has to build new programming to meet the needs and separate housing needs from mental services, which is very difficult,” she said.

Swager said those efforts grew after the 2019 announcement, but added that this growth “rapidly had to shift with the pandemic.” In-home visits, for example, halted when the pandemic began. And in-person connections of all kinds declined and slowed.

“What we have is (a) giant hole of need in the middle between residential/inpatient and ambulatory and the system is trying to build out the middle right now,” Swager said. She said healthcare providers are making progress, but it’s tough when more kids are “coming to care in a system that was already broken and trying to rebuild.”

Multiple providers told me about waitlists and trouble with recruitment and retention, which I’ll be describing in more detail in an upcoming post.

Swager noted that children in West Virginia are experiencing a mental health crisis along with the nation’s children. But she added that in Appalachia, that crisis has been ongoing for a decade.

She pointed to several contributing factors: the substance use disorder crisis, the pandemic, and the “DHHR crisis with out-of-home placements.”

Before kids were losing adults and guardians to COVID-19, they were losing them to overdoses, incarceration and lost custody. Some experience generational trauma, Swager said, which refers to the “transmission (or sending down to younger generations) of the oppressive or traumatic effects of a historical event.”

Like other providers, WVU Medicine is seeing an increase in children needing help, particularly in the emergency room – mainly kids with depression, PTSD, and particularly high rates of anxiety. Swager also attributed the increase to “worsening behaviors” exacerbated by pandemic-related isolation and loss of routine and structure.

What can be done?

Earlier this week, I listed some ways parents and kids can address mental health problems.

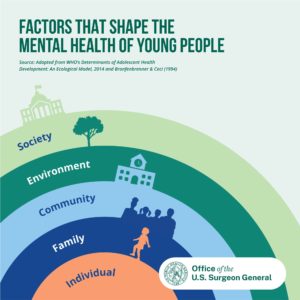

The surgeon general also recommends ways employers can help, including by providing “access to comprehensive, affordable, and age-appropriate mental health care for all employees and their families, including dependent children” and by providing paid family leave and sick leave where feasible.

The surgeon general also recommends ways employers can help, including by providing “access to comprehensive, affordable, and age-appropriate mental health care for all employees and their families, including dependent children” and by providing paid family leave and sick leave where feasible.

The surgeon general report also recommends employers:

- Consider additional employee benefits such as respite care for caregivers and mental health and wellness tools.

- Help caregivers secure affordable childcare, or offer more flexible work arrangements.

Healthcare providers can also aim to serve the whole family and the whole child by screening for problems like food and housing insecurity, while government officials should ensure kids “have access to mental health services in community settings whenever possible; and (avoid) unnecessary placements in nonfamily settings,” the surgeon general’s report states.

Mental health conditions that lead to crises are also treatable. Get help:

From HELP4WV: “When it comes to children, it’s easy to see that something is wrong, but scary and difficult to know where to look for help. We are available 24 hours a day and seven days a week to assist in finding the most appropriate and available treatment for an array of youth behavioral health needs. From parenting support to immediate crisis response, contact 1-844-HELP4WV to talk to a trained Helpline Specialist who can help you understand options and link you directly to treatment providers.”

If you’re in crisis, get immediate help: Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273- 8255, chat with trained counselors 24/7, or get help in other ways through the Lifeline.

Read the previous posts in this series:

COVID-19 caused more chaos for struggling WV children

Vaccines, civil rights, misinformation: political problems harming kids’ health, too

1 Comment

Kayla · December 21, 2021 at 3:07 am

CSED Waiver has been implemented in the state of WV with many of those providers going into homes and providing intensive services and supports. As with any implementation of programming there have been challenges, including the pandemic, but the Waiver has provided stability to many children and their families. Hopefully it will continue to develop and help keep children in their homes and communities.